No Man’s Land

10/29/2013

Portugal / 2012 / Portuguese

Directed by Salomé Lamas

“I believe in God and Jesus. I think everything else is a lie… and now, about Jesus, I have to think twice.”

“I believe in God and Jesus. I think everything else is a lie… and now, about Jesus, I have to think twice.”

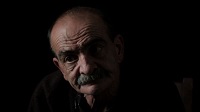

A picture of the marriage of raptor and ape, with piercing eyes and heavy strength in his hardened knuckles, he sits comfortably in the interview chair. He folds his arms, shrugs impertinently, and holds masculine postures as he talks without ornamentation. Heavy-mustached, wearing jeans and a sweater, it isn’t obvious that he lives on the streets, drifting on the periphery of the city. Meet Paulo de Figueiredo, a one-time paramilitary in Portuguese Africa, later a hired killer for the Spanish secret police and for the CIA in El Salvador. For him, he says, killing is “like drinking a glass of water.”

“I never eliminated decent people, people you could call People. I always eliminated those who are no good.” We wonder why we are hearing his story, why we are paying attention to the musings of the aggressor, the agitator, the oppressor. Filmmaker Salomé Lamas is not aiming to tell an untold story, but to examine how human beings perform their past, and how the telling can be a means to come to terms with it. Unrepentant as he is, he is far from unreflective, or mindless or cold-blooded. Indeed, we are seeing how philosophical someone like that can become, and how that helps them commit murder, and go on to live with the results. The justifications are more complex than he lets on, harbors of human reality, doctrine and myth.

“My first job was against the GRAPO [a Spanish Maoist organization], to liquidate an individual in Lille.” The official words for what he did (“liquidate an individual”) have been assimilated to varying degrees, and sit uncertainly beside his personal ideas. Spain’s furtive war with the Basque separatists gave him good justification for what he did. His targets were always precise, he claims, and he never got the wrong man. This seems to sit much easier with him than the murder of innocent people in the messy guerrilla wars in Africa in the 1960s and 70s, which comes across heavy with dissonance. Even he seems horrified by what he saw and was commanded to do there, but it began his life of officially-sanctioned killing.

“I evaluate the person and make the price. In the case of the GAL [Spanish secret police], it was 10 million pesetas per man killed.” The monetary measurement itself is a coping mechanism, to begin with, and initiates the distancing that helps him commit murder. It’s not an abstraction – quite the opposite, he seems to have reveled in the intimacy of it – but an “othering” of his victims that reinforces a personal notion of humanity. He answers his own question – “how much is a man’s life worth?” – with a question: “…men like me, or men like them?”

[Room-tone].

“Then I started my life as a mercenary. I liked the army, I liked killing, and I liked seeing blood. But always for the truth, never for pleasure.” The members of the Basque ETA whom he helped eliminate were evil people, in his estimate, responsible for innocent deaths, and labeled as terrorists. So any measure taken against them, extra-legally, is apparently justifiable. He cranes his neck out, lifts his eyebrows, and speaks with eerie clarity – all of his movements, from the spontaneous to the purposeful, with a mechanical severity about them.

“The blood and gunpowder are like cocaine and heroin. They get into your blood.” It is not Lamas’ task to reveal the details; Paulo does this himself. What she does is create a space, both physical and cinematic, through which we encounter this character. It is as much a performance space as an arena for a personal reality to occupy. Lamas isn’t Claude Lanzmann, and this film isn’t about producing evidence, about revelation, about proving this, that, or the other. Since so little disclosed evidence exists at all of GAL’s operations, Paulo himself is the only statement on his career, and he is here to spill his guts willingly. Unlike Susana de Sousa Dias’ film 48 (2009), which uses only still photographs and audio interviews to tell the stories of the victims of Portugal’s decades of government repression, No Man’s Land is about the living, breathing encounter – marked with expression and direct address. Here, Paulo’s metaphors, evasive statements, and dismissals of details as “irrelevant” – all of which speckle his interviews – function just as vividly as his plainspoken anecdotes.

“The blood and gunpowder are like cocaine and heroin. They get into your blood.” It is not Lamas’ task to reveal the details; Paulo does this himself. What she does is create a space, both physical and cinematic, through which we encounter this character. It is as much a performance space as an arena for a personal reality to occupy. Lamas isn’t Claude Lanzmann, and this film isn’t about producing evidence, about revelation, about proving this, that, or the other. Since so little disclosed evidence exists at all of GAL’s operations, Paulo himself is the only statement on his career, and he is here to spill his guts willingly. Unlike Susana de Sousa Dias’ film 48 (2009), which uses only still photographs and audio interviews to tell the stories of the victims of Portugal’s decades of government repression, No Man’s Land is about the living, breathing encounter – marked with expression and direct address. Here, Paulo’s metaphors, evasive statements, and dismissals of details as “irrelevant” – all of which speckle his interviews – function just as vividly as his plainspoken anecdotes.

The film’s title describes several “no man’s lands”. One is the open field of life and death occupied by the nationless, colonialist thugs. (Paulo says that the ‘Carnation Revolution’ of 1974 failed to reach them in Africa). Another is the post-urban weedscape that he now inhabits. And a third, more elusive frontier could be that of life and death, the border between which could be wider and more uncertain than we may have imagined. Paulo asserts that he probably should have taken his own life – but we are only brave when it comes to the lives of others. While the subject talks through walls of invention and creation, the unadorned room itself is examined as both a product and facilitator of artifice. Set in an abandoned palace, it is as though the interview is coming from a seat of fallen power. It feels as though Lamas is deconstructing the place all the while, challenging its positioned neutrality, depicting it empty, blasting it with over-exposed sunlight.

Paulo talks in a matter-of-fact way about the things he has done, because to him they represent a matter of fact, not only a part of an unmovable past, but having happened due to the unchangeable ways of the world. Nonetheless, multiple layers and contradictions begin to intersperse. His attitudes seem to change significantly from his time in Africa, where Portugal was fighting guerrilla warfare, and his later years spent working for GAL. In his early career he helped with extensive slaughter of human beings, including women and children. He then describes being back in Europe, and forgoing the assassination of a target because the man’s wife and child were in the car with him. Later, when the man returned to the scene alone, Paulo completed the job.

He insists that he killed not for money (although he liked money as well), but for his “revulsion for cowards.” Those who have never committed murder are now faced with the primitive ancestor of the cold-blooded hit-man, someone defending a Manichean structure of the world, literally killing for it. Perhaps a more nuanced characterization would be that this “revulsion” allowed him to do it so easily, rather than drove him directly to it, since his faith in that view never seems to have wavered. It’s a rags-to-riches story of the colonial refuse shipped to Africa to wipe away rebellions. But his story ends in rags rather than begins with them; Paulo evidently came from a rich, conservative family. Climbing the ladders, becoming a favorite of the secret police, was a pretext used so as to never have to give up violence and rejoin normal society. And now he never seems to have done so, and thus can speak openly and good-humoredly about his past.

He insists that he killed not for money (although he liked money as well), but for his “revulsion for cowards.” Those who have never committed murder are now faced with the primitive ancestor of the cold-blooded hit-man, someone defending a Manichean structure of the world, literally killing for it. Perhaps a more nuanced characterization would be that this “revulsion” allowed him to do it so easily, rather than drove him directly to it, since his faith in that view never seems to have wavered. It’s a rags-to-riches story of the colonial refuse shipped to Africa to wipe away rebellions. But his story ends in rags rather than begins with them; Paulo evidently came from a rich, conservative family. Climbing the ladders, becoming a favorite of the secret police, was a pretext used so as to never have to give up violence and rejoin normal society. And now he never seems to have done so, and thus can speak openly and good-humoredly about his past.

“For great evils, great remedies.” His words form a sort of episodic odyssey, chaptered out into long, non-digestible aphorisms. They could accrue into a disturbing little book of quotations, like All I Need to Know I Learned From a Portuguese Mercenary. And from them a presumably secret rationality emerges, subtle philosophies of life and death given a plain, brutalist structure and form. One can imagine him relating his parps of wisdom over an espresso at a Lisbon café. Lamas guides the days she sat with Paulo with general questions, but allows the picture to more or less materialize on its own. Of course it’s a lumpy, distorted picture, with events misplaced and large parts omitted, but with implications from and about reality shining through the cracks.

As easy as it is to think of Paulo as a protagonist in the story, the depressing feeling that starts to accumulate from the very beginning (and builds as the film progresses) is how insignificant he is in the story of the secret police and paramilitary organizations whom he served. At the level of his experience – the entire substance of his story – he was granted a lot of power over human life; he was a turn in the road, guiding them with professional suavity from into death. He was used for this purpose and nothing else, and then cast aside, littered by the society that created him and forgotten about, along with the suppressed documents about the political murders themselves. Even as he talks as though he used Salazar’s and then Gonzalez’s government to earn a living and to have a little fun doing so, it is evident that he is a tool of those powers.

There is a film that one is reminded of, Massacre (a collaboration by Monika Borgmann, Lokman Slim, Nina Menkes and Hermann Theissen), made in 2005, in which a handful of supposedly real perpetrators of the Sabra and Shatilla massacres are interviewed with their faces obscured by shadows and underexposure. In that film there is something about the anonymity of it, of being interviewed individually, alone in the room, that draws out the truth, like a serum. There are differences, of course; Paulo is a relic of a time of impunity, and so relates his story with brazen transparency. There’s also an ease of conscience over his activities, that he was always in service of the right thing. The Sabra and Shatilla killers, on the other hand, murdered untold numbers of Palestinian civilians in refugee camps, and their justifications are strained, unbelievable even from a right-wing, militaristic vantage. Both films are about narrative, about staging the consciousness of murderers, about experiencing them as forms in a room. We don’t gain any sympathy for them, or see things from their perspective, but for once are treated to their perspective, no longer hidden, anonymous agents of the state who disappear after having finished their job.

The largeness and unknowable mystery of the wider narrative is what makes this glimpse into it truly scary, and how all of it boils down into the conscience of the crouchant contract-killer. Paulo’s stories (heard in fragments that are at once lucid and disjointed), at the end of the day, are his own, and while they say a lot about the political climate of his time, they are also only the tip of the pistol. It’s not a smoking gun, but it is gunsmoke, in a sense. And about what was actually going on behind the curtain, his knowledge of it is just as clouded as the next individual’s. He knew not to ask questions, only to name his price, do his job, and disappear.

The largeness and unknowable mystery of the wider narrative is what makes this glimpse into it truly scary, and how all of it boils down into the conscience of the crouchant contract-killer. Paulo’s stories (heard in fragments that are at once lucid and disjointed), at the end of the day, are his own, and while they say a lot about the political climate of his time, they are also only the tip of the pistol. It’s not a smoking gun, but it is gunsmoke, in a sense. And about what was actually going on behind the curtain, his knowledge of it is just as clouded as the next individual’s. He knew not to ask questions, only to name his price, do his job, and disappear.

In the second piece of the film’s coda, when it bursts out of the darkened room and beneath a bridge where homeless men negate their label, Paulo becomes peripheral, but his story, if it can be called one, gets updated. He gains complexity, beyond being a character, a voice commenting on history. We see a jocular and rather tender interaction between him and one of his fellow bridge-dwellers, a black man who plays a broom like a guitar. Lamas mentioned that, in spite of being extremely right-wing and racist, Paulo helped the mentally ill man with his immigration papers. This little vignette with the two of them is Lamas’ way of de-constricting our view anew, unsealing the claustrophobic room and once again seeing how people have their layers. While his stories relate a doctrine of black-and-white, of a forcibly narrow worldview, we are reminded upon leaving that they too must mingle with everyday life just as any others.

While the idea of giving a shape to history through the words of the perpetrators is something that No Man’s Land has in common with The Act of Killing, the approach here is one of depleted artifice. While the other film is about the limits and pitfalls of how one’s imagination mediates the knowledge of past deeds, Lamas’ interviews with Paulo are all about his sounds, gestures and mannerisms, and how the man exists in the immediate camera-space. Rather than being a reduction, however, its intimacy affords it a sensory density, as it navigates Paulo’s flow of anecdotes and opinions heavily laden with details. The smallest facets become clues, impressions all leading to the void, and yet only exist in front of the camera, fading back into the urban scrap heap where the mercenary has been deposited by history.